June 26 2025

Part 2 of my series about genocide

Genocide and the Middle East

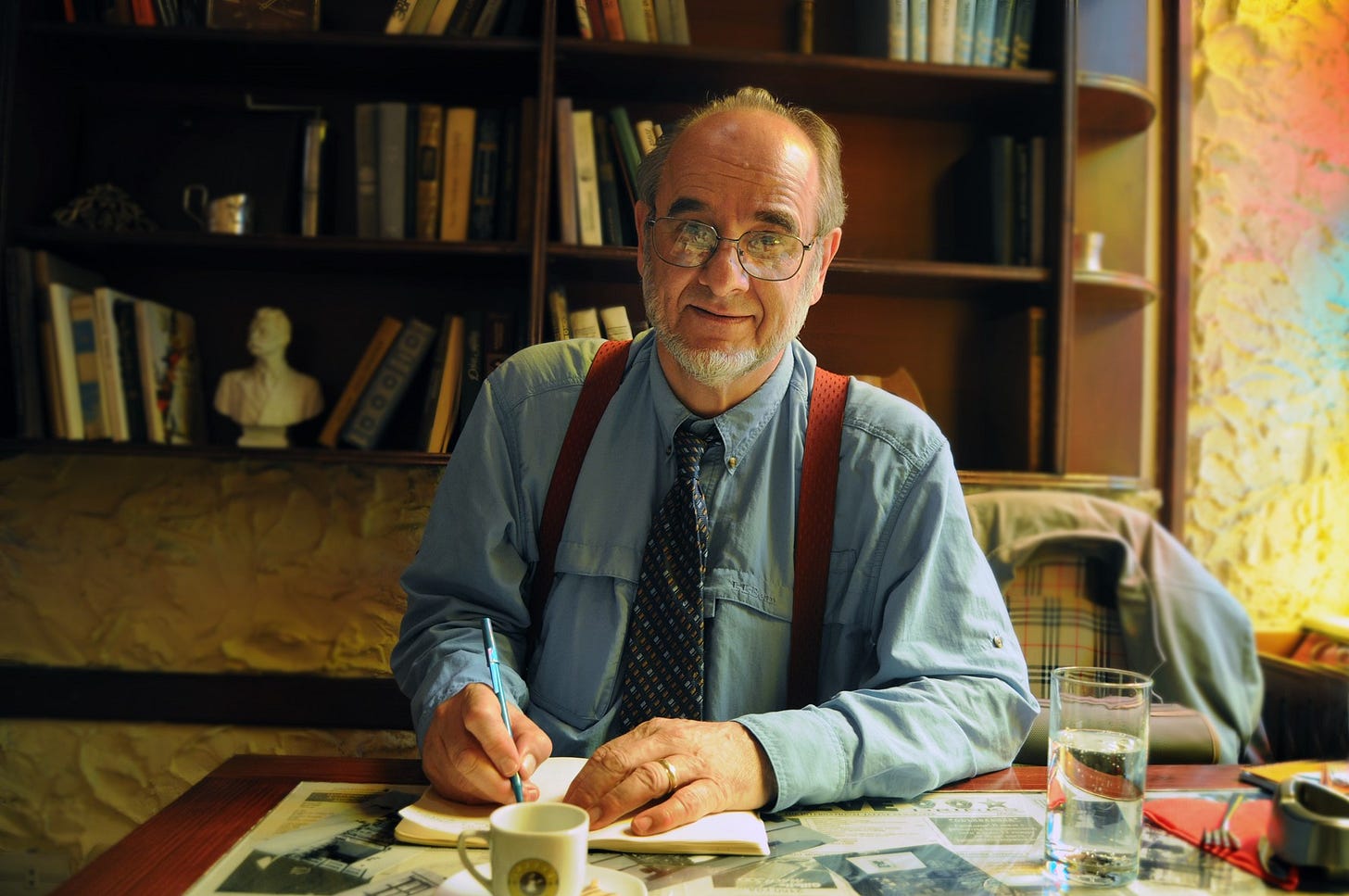

Heidi Kingstone interview with Alan Whitehorn, genocide scholar and professor emeritus, Royal Military College of Canada

Genocide has become the issue of our times since Hamas’s attack and Israel’s subsequent response. This conflict has defined our times. Why has this intertwined tragedy galvanised people on both sides of the conflict and worldwide in a way that many others haven’t?

I don't think I can do this without addressing what's going on in Gaza, and it’s all the more reason for people to stand up and do more. It can feel like needing to tear down a huge mountain, but you feel that you can’t do it on your own. You perhaps say that it is an enormous, overwhelming mountain, but at some point, people will have made a preliminary path. That travelled, hazardous path is based on the bravery and the dedication of people from before who said, ‘Well, that looks pretty hopeless, but I'm going to try nevertheless. ’

I think that's the attitude you need to have. I will probably not live to see the solution to the cascading crises of the contemporary Middle East, but people seeking justice have to start with the first brave and difficult step. You never know when an authoritarian regime is actually on the brink of collapse - the Russian Revolution of 1917, for instance, or the collapse of the Communist regime in 1991 - people often didn't anticipate those events.

So, to answer the question. I’d say yes and no. I think we often tend to overestimate the uniqueness and the importance of this moment.

People aren't very good at recognising the early warning signs of genocide and taking sufficient remedial action. It's only when you see horrific mass deaths and starving orphans that people react, but after the fact. The complex genocidal process is still unfolding, but you know horrific, murderous deeds have already occurred. So we are currently at a critical time, but I think there have been other such times, so I don't see today as unique.

And for those of us who've been involved in genocide studies, sadly, this is not the first time around the difficult course. Genocide studies evolved in earlier decades out of Holocaust Studies, so obviously, calamities involving the State of Israel, the global Jewish population, and the population in Israel are going to have an impact on genocide studies.

A number of pioneers of genocide studies were Holocaust survivors. It was easier in the past to raise money for Holocaust studies than for comparative genocide studies. Historically, there has been a foundational link between the Holocaust and genocide studies; early on, the debate centred on the Holocaust’s uniqueness. Most genocide scholars have moved beyond that. Genocide studies have become comparative, more so in recent decades, with younger scholars looking further afield. In the past, research and writing were somewhat Eurocentric, both in terms of the demographics of those involved and still are, but we are now seeing more case studies from around the world.

There is an interesting reframing from the title ‘Holocaust and Genocide Studies’ to switch to the phrasing sequence of ‘Genocide and Holocaust Studies’, suggesting that the comparative framework should be more central and the field less skewed to a single case study. There's no doubt that, if you look at the films and the books, overwhelmingly, the majority of writings on genocide have been about the Holocaust, particularly works penned in English.

A cautionary note is to remind ourselves that genocide is not the only urgent global crisis. If we are to survive as a species, we must move beyond hyper-nationalism and recognise that we are a global community. The Doomsday Clock is moving closer to midnight. It’s a dangerous and increasingly heavily armed world overflowing with conflict. We have to overcome our fear so as not to be immobilised. We need to encourage ourselves and others to do more.

We have bystanders, perpetrators and collaborators. Are bystanders guilty of crimes?

Bystanders, perpetrators and collaborators are the three prevalent psychological labels in an analytical model in genocide studies. Bystanders are usually considered the largest group that is sought to be won over, either by the perpetrators or by the victims. The fate of the victim is largely determined by whether or not the bystanders get involved to help provide sanctuary or to take up genocidal acts. There is a strong correlational linkage between genocide and war. Such wars may be local, civil, regional or global.

So, are bystanders guilty of any crime? To explore this theme, I often cite the example of a drowning child. Imagine you are walking on a path, and you see a drowning child, but you choose to do nothing. If the child dies, are you guilty of the death of that child?

The manner in which the child entered the water is a crucial factor. However, you are also a witness and a potential rescuer. Do you turn away, or do you move closer and provide a helping hand? So now we expand from the example of one drowning child to the enforced starvation of children who are constrained to a confined area by a hostile, external military force. The example that comes to mind is the Warsaw Ghetto in the 1940s.

The rest of the world saw images, but it was Eastern Europe, not Western Europe, not North America. We, as outsiders, did too little, too late. Decades later, in a different century, sadly, it seems the same issue exists with the civilian population in Gaza.

There are starving children trapped in a territory where its borders are closed by a powerful external military force that has resulted in significant ways in an imprisoned civilian camp. This is what the Warsaw ghetto was, and the parallels to Gaza are striking to me.

We know that the fate of the Warsaw ghetto was horrifically brutal. Today in Gaza, we are seeing vast numbers of massive bombs supplied by the American government to Israel that are being used to demolish whole blocks of apartment buildings in Gaza. Also profoundly problematic is the partial blockade, or even the cessation, of food and medical aid at times.

If we do nothing, we are bystanders who have not seen the worst, but we've surely seen more than enough to warrant the action of assistance as human beings, parents, grandparents, and scholars. We're not as guilty as the perpetrators who are putting the bombs on the planes. We're not as guilty as the commanders who make the decisions to drop the bombs or the politicians who say, “Do it. I don't care about the human cost. I want total victory.’

This is the language of Hitler. The minute you talk about ‘total victory’ over other people, you are potentially moving heavily into the genocidal realm because total victory has the clear connotation of annihilation. Whether it's domestic politics or international politics, the notion of total victory is the notion of conflict without boundaries.

In the end, I suppose we could say: ‘We're all guilty in life. The question is, how much?’

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, numerous genocides have occurred. What have we learned? Why can’t we stop the hate and the butchery? Why have genocide education, media coverage, museums, memorials, libraries of books, movies and TV series not made enough of a difference?

What have we learned? Not enough, clearly. Intergenerational knowledge is not necessarily effective in transferring important insights about the lessons of war, conflict escalation, and the risks of not acting soon enough.

It is also far easier for humans to be fearful than to love. This is US President Donald Trump's key insight into human nature. He draws upon the mass psychology of fear. Fear is how we survive as a species. It is harder to trust and to love, but that is what we need to do to thrive and develop as extended communities and civilisations.

We need to love and to nurture, but our survival orientation is often one of fear and apprehension. In ancient times, it was the seemingly unknown hostile Nature that we attributed to a powerful, vengeful god. Historically, whenever we came across people who spoke a different language, looked different or had different customs, it was harder to find potential affinity. We see that with the public reaction to waves of immigration. The fear comes from a kind of ignorance, not necessarily prejudice, but distrustfulness. So, it is harder to find and establish trust.

Conflict with others, however, is more likely than cooperation. Prominent anarchist theorists suggested that conflict is not the key to species survival; it's cooperation. Conflict is not necessarily preeminent; perhaps cooperation is. It’s just that our newspaper headlines proclaim war is declared, as opposed to, yet again, the babies being cared for day after day. What we publicise and what we do routinely are often not the same things.

The rise of authoritarian leaders is more problematic in part because the weaponry of war is getting far more dangerous. War is becoming more lethal, weapons more precise and can be cheaper, allowing massive swarms of new deadly drones. The technology is also more readily available to more countries and, of course, rogue states. So, it’s a double whammy. Authoritarian leaders per se are a problem, but when you change the dynamics of warfare technologically to make the world less stable and conflict more dynamic and more dangerous, then that's a worrisome combination.

So, it's an interesting argument, this conflict versus cooperation in human nature. We have both. And the question is, what is the mix? Under Hitler and Stalin, a massive global conflict unfolded in the form of World War II. Under Trump and Netanyahu, there is also now an increase in conflict. However, under other visionary state leaders in the past, such as Franklin D. Roosevelt, along with his wife Eleanor, a humanist aspiration emerged to create a new global governing assembly in the form of the United Nations. Accompanying this new international level of government, a universal declaration of human rights was proclaimed in the shadow of what had been a devastating global war.

Can we say some genocides are worse than others, both in scope and magnitude? The Nazis perpetrated the Holocaust, what is still considered by many the worst crimes against humanity the world has ever seen.

In fact, the worst genocides in global history are the centuries-long global colonial movements. They were collectively a global process of imperialist, racist aggression and domination, and often linked with brutal, dehumanising slavery. Untold numbers, certainly hundreds of millions, perhaps billions, died. I don't know how accurately we can tally the centuries-long enormous number. Columbus alone killed vast numbers of men, women and children; even entire communities were ravaged. Many other Conquistadors followed after him in the name of the King of Spain, the King of Portugal, or a king of another European country.

It was not only the violent conquests and mass killings upon first contact, but also included the creation of enduring, brutal colonial conditions that led to generations of oppression, undue poverty, enormous suffering and unnecessary mass deaths. Genocide by attrition is harder to see, but its impact may be as great or greater and certainly spans a longer time period.

How and why has the term genocide been weaponised?

In the early years, when there was little discussion of genocide, it wasn't really weaponised as much because the dictators didn't know the term or seem to care about it. But now, even Putin, Netanyahu and other autocratic leaders realise this is an oft-cited and powerful word. The label can be employed in state propaganda by claiming that the perpetrator was, in reality, the alleged victim and they are just responding to aggression by others.

The term has certainly become more prevalent in journalism and scholarship, and we are seeing different ethnic/religious groups and regimes start to use it in one rival state versus another.

In the South Caucasus, the Armenians noted that the Azeris had engaged in genocide. The Azeris replied that Armenians had committed genocide. In fact, in the different wars between each other, the Azerbaijani and Armenian states committed war crimes and crimes against humanity. Whether it is genocide requires further analysis.

In the early 1990s, both Azerbaijan and Armenia engaged in what we would call ‘ethnic removal’ of minorities from the lands each state controlled. People tend to use the term ‘ethnic cleansing’. I don't employ that phrasing. I think it's a loaded term, incorporating and repeating a genocidaire’s world view. I prefer the academic labels ‘ethnic displacement’ or ‘forced relocation of an ethnic or religious community’, which usually involves a minority.

The term, genocide, has sometimes been weaponised, as we explore historic eras. Suppose a nation/people have suffered genocide in the past, such as the Armenians in 1915. Could they commit genocide in the South Caucasus at the end of the 20th century, in the liberation of Karabakh from Azerbaijan? Armenians were strongly inclined to say, ‘no, we couldn't do it because we suffered genocide in the past’.

Since Jews had endured and suffered so much historically, and so many of their community members had died during the Holocaust in World War II, many Jews fled Europe after the war. They felt that they would never be safe in Europe again and concluded that they needed to create a state elsewhere that would protect Jews collectively in the State of Israel. The analytical dilemma is that there are at least two different entities: a people and a regime. People as a whole may not commit genocide, but a regime might be engaged in acts such as war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. Who is responsible? Is it only one particular administration, a regime or an entire population/nation that allowed the government to come to power? Who is ultimately responsible?

Certainly, the issue can be traced back to foundational, constitution-making periods. A regime can be established in a manner that targets either internal or external groups that don't align with a perceived model of the ideal state and its constituent citizenship. And historically, we can talk about the white settler colonies that excluded non-whites from citizenship. Similarly, we can explore the expulsion of the Palestinians in the founding of the Israeli state, let alone the expansion of the Israeli state.

Going back to the original question, I think the dilemma we have is the following: Can a people who have suffered genocide in previous generations commit genocide in subsequent generations? I think the pessimistic scholarly answer is yes. This is partly because the lessons aren't sufficiently learned, or the wrong lessons are learned. For example, if you were a targeted victim in the past and have a fervent desire to never be a victim again, you can become hyper-vigilant and more militarily prepared to fight right away. And if you are hostile enough to some other population, it is possible for a people who have suffered a genocide in the past to commit genocide in the future. And we can add another academic observation: ‘Under terrible conditions, most of us are capable of genocide’. If people are terribly fearful, suffering enough and passionately believe that they have to urgently protect their clan, they might conclude: ‘I’m going to make a pre-emptive strike because the other nation has and continues to harm me. It is an ever-present, ominous existential threat that must be destroyed.'

We often see genocidaires saying, ‘well, I had to do it, because otherwise they would have killed us or harmed us’. That is, in essence, Trump's message about Hispanics and other immigrants. Governments have realised that one of the potential ideological defences is to say, ‘No, we're not committing genocide. The other ethnic group or regime is.’ So, the term has been weaponised, and, like any word, it can be used constructively or destructively. We need to disentangle criticism of a state vs hostility to a people. They can go together, but they don't need to go together, unless you force them into your analytical categories to say, well, one implies the other or one defines’

I'm old enough to remember that several decades ago, most people in Western Europe and North America viewed Israel as a benevolent and hopeful state. A place for survivors of genocide to live, recover and eventually prosper. Today, to many outsiders, particularly amongst the younger generation, their view is somewhat different. The older generation remembered World War II and the Holocaust. To the younger generation, it is, to a significant extent, a distant part of history. The plight of the Palestinians is more in the news.

The expansionistic policies of Israel initially seemed militarily and politically successful, but contained a tragic flaw that is now increasingly revealed. Just because you can take the land, it does not mean the land will be yours forever, or the subjugated people will accept it indefinitely.

Since 2005, I have often travelled to the South Caucasus. In the late 1980s and early 90s, Armenia and Azerbaijan fought over Karabakh, the Armenian enclave that had been under Azerbaijan's control in the Soviet Union. When Azerbaijan claimed its political independence from the USSR, it never successfully controlled Karabakh and tried to crush the Karabakh Armenian population’s independence movement. The Armenians fought back, and partly because of the disorganisation amongst the elite in Azerbaijan, the Armenians not only won their independence, but they also claimed other land and displaced many Azerbaijanis. To Armenians, this was their security corridor or buffer territory around Karabakh. This was much like the state of Israel, which had occupied the adjacent land around its border as a security zone. However, in the long run, such geo-political thinking has come back to haunt both regimes. They created a permanent or almost permanent enemy amongst all those displaced people who felt anger and hatred against the state of Armenia. It is similar for the state of Israel.

And thus, we return to the topic of bystanders. Are they guilty of ignoring the mass suffering and death of so many displaced others? Are all those who tolerate, accept or promote the expansion of Israeli state territory guilty to some degree? Is each travelling somewhere along the path of the ‘sin of indifference’?

I wanted to call my book ‘Fear, Greed and Propaganda’, as those seemed to be the key motivators driving genocide. What links all genocides in your opinion? How are all genocides different but the same?

I never really liked that proposed book subtitle because genocide is so much more than several of those traits. Certainly, greed and envy can indeed be factors contributing to genocide. During the Armenian Genocide, the Turkish locals and Muslim neighbours quickly grabbed the goods of the expelled Christian Armenians, who were forced by state decree to leave their home cities and villages within 48 hours. The transfer of goods is often a big financial component of genocide. Genocide can be perceived as good for the business of perpetrators and their supporters but at the expense of the targeted ethnic/religious minority.

However, to understand genocide, greed is in many ways a secondary motivator. One must first explore fear and dislike of others and outsiders, which are turned into hatred and hostility. Adding to the deadly mix are a sense of crisis, growing authoritarianism, leading to despotism and misuse of the military against a civilian-targeted population.

‘Coveting a neighbour's property is not that unusual, but the opportunity to do so is greatly accentuated if there is also anger, hostility and a sense of blaming a neighbour. Many people may express fear and greed, succumbing to propaganda, but that doesn't necessarily make them genocidal. These proclivities are components, but not sufficient motivators. Ultimately, prejudice is at root to blame.

Before U.S. President Trump was able to initiate many of his policies, he had to create and stir up fear; fear of the outsider, fear of the foreigner within our ranks. Often, a distinctive minority is an easier and more convenient target.

In Khmer Rouge Kampuchea/Cambodia, the so-called ‘foreigner’ was perceived to be not truly Cambodian and became a target. Initially, it was the ethnic minorities, particularly the Vietnamese, but soon even Cambodians, who had been allegedly corrupted in the cities, were targeted. The truly pure Khmer were said to be only those from the countryside.

The factors contributing to genocide are complex and multifaceted. Amongst them are: a lack of understanding others, an absence of compassion for others, experiencing a major setback that you blame on others, a charismatic leader directing a dictatorial regime that fosters hateful propaganda that targets a victim group. Of course, there will be some who are not ‘true believers’ in the genocidal malevolent vision, but are economic opportunists who jump at the opportunity for ‘free land’ ruthlessly confiscated from others. The chance for a free cow, goat, rug, household furniture, farm or orchard can be quite tempting to many. So, economic factors play a role, but ultimately, not the most pivotal one.

What are the conditions in which genocides become possible?

As I mentioned earlier, the factors are multiple, but the roots can all be traced back to the human condition of distrust of the outsider and fear of the other.

Ben Ferencz was the youngest prosecutor at the Nuremberg Einsatzgruppen trials. He was 27 when he stood on the podium to give his opening address. He died a few years ago at 103. I interviewed him when he was 101, and found him remarkable and brilliant. Talking to him was a true link to history. Despite, as he said, ‘peering into hell’, he never gave up hope that the world was inching forward to a better place. Some called him naive, others believed that he was an inspiration. The world is in a grim and dangerous place, sliding towards authoritarianism. What can or should we do?

Ben Ferencz was a wonderful, inspirational figure, and his lesson was to never give up.

Even in the death camps, we saw some people survived better than others, partly because of their attitude, and here I'm thinking of Viktor Frankl, the Austrian psychiatrist who wrote Man’s Search For Meaning. He noticed that men who gave away their last piece of bread or comforted others survived the longest, embracing whatever part of humanity they could hold on to.

Holocaust survivor and Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal had been a young prisoner at Auschwitz when a Nazi official, on his deathbed and haunted by his deeds, asked the Jewish prisoner for forgiveness. The young Wiesenthal said no. Years later, in his book The Sunflower, Wiesenthal revisited the question and asked 53 internationally distinguished persons how they would have reacted to the situation. Their replies were profound and varied.

Wiesenthal and Frankl were famous, illustrious Holocaust survivors. They went on to achieve great things but could have said, ‘Well, I've suffered enough. I'm not doing anything else.’ But instead, they chose to remain engaged in the ongoing human struggle for a better world. Wiesenthal pursued those perpetrators guilty of genocide, while Frankl counselled us to transcend despair and to look for hope and humanity. Both, in their own way, were seeking justice and endeavouring to overcome evil.

How and why did you get involved in your field?

It started with my metzmama, my grandmother, who survived the Armenian Genocide and lived in refugee camps and orphanages for over a decade. Many years later, I was being confronted on a repeated basis by state-sponsored Turkish genocide denial and felt an obligation to respond.

I had been doing archival work about my family history and what had happened to the Armenians in 1915, as reported in accounts in Canada’s national newspaper, the Globe and Mail. Afterwards, I read a new letter to the editor about the current Turkish regime’s continued denial. This appeared in the same newspaper where I had been reading archival documents about the historic genocide. As a response, I wrote a letter to the newspaper that was published. The next thing I knew, I was invited by the Greek Canadian community to give a paper at a conference on ethnic minorities in the Ottoman Empire. I co-authored a presentation with fellow academic Lorne Shirinian. Afterwards, our two conference chapters became the core of our jointly published book, The Armenian Genocide: Resisting the Inertia of Indifference. The book included our analytical essays, archival documents and some of our genocide-themed poems. After that book appeared, my life and career were forever changed. More lecture invitations and published books followed. As a result, it became a life of writing and speaking about genocide. Sadly, the need to continue to do so has not diminished.

What key lessons have you learned?

We can draw many lessons. Perhaps a key surprise is that most of us are capable of harming others in extreme conditions, perhaps even to the point of genocide. So the lessons are intertwined. Our human nature is both conflictual and cooperative. We need to realise that under the wrong conditions, we are capable of great harm. But under the right conditions, we are capable of much goodness. We need to choose and choose wisely.

***